For the past few months, The Toughest Beat has been attempting to inform people of the increase of violence inside of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) prisons. Using data from CDCR, The Toughest Beat has shown a regular increase of violence from inmates against staff inside of CDCR’s facilities. Although CDCR refuses to report honestly about the real living and working conditions for the inmates and staff inside of prison walls, we hope making this information available helps lead to positive change.

After making a few posts trending the rising staff threats from inmate violence, many readers asked to compare this data against California Model prisons. This was found troublesome as the California Model of prison management is ill defined, using catchwords to describe vague policies to make prisoner’s lives happier. Although some prisons officially stated they are using the California Model, many CDCR prison managers in non-effected prisons implemented programs/polices they think were aligned with the California Model. For example, non-California Model Prisons are using the Model as an excuse to have inmate BBQs and game days with inmates.

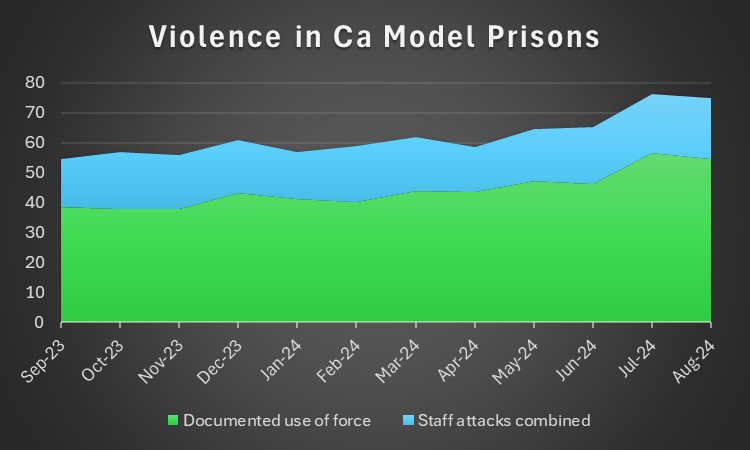

Recently, CDCR announced issue#1 of the California Model Magazine. This propaganda device is an attempt to push the California Model to more prison staff. The magazine touted eight prisons as already implementing the California Model. The Toughest Beat went to the CDCR report statistics to measure any impact the California Model had on these prisons. We found that inmate population decreased state-wide but the documented use of force incidents In California Model prisons increased, additionally staff attacks increased slightly. It should be noted, violence in CDCR increased in every aspect to include non-California Model prisons during the same period.

This chart took the averages of documented incidents in California Model prisons where staff were required to use force and documented incidents where staff were attacked by inmates. The prisons used for this average were SVSP, VSP, CCWF, COR, RJD, SAC, SATF, and SQRC. These prisons were advertised by CDCR as being in the California Model. The data did show a decrease in violence form July 2024 to August 2024, but an increase of violence overall.

It is hard to find an official start date for California Model prisons as the policies are being made-up as they are implemented. Governor Newsom did officially announce a commitment to the California Model on March 17, 2023. According to the propaganda California Model Magazine, SVSP, VSP, and CCWF were the first Model sites, with COR, RJD, SAC, SATF, and SQRC starting in May 2023. In January 2024, all CDCR staff were forced to have training on the California Model. This author also attended this training where no policy specifics were given, only a strong message to be nicer to inmates and give inmates more freedoms.

The writers of The Toughest Beat have been very critical of the illogical rollout of the “California Model” of prison management. California attempted to sell the California Model to make inmate’s lives better. Later, after some backlash, CDCR management is now pretending the California Model is to make staff lives better. The California Model of prison management is not based on any real criminological studies and developed by people who only used a biased idea of what they understood of the Norway Model. The bias behind the California Model is to give inmates more freedom and give inmates more fun activities. Despite the deception by CDCR management, no other real processes were changed by the California Model of prison management.

After some backlash from the public, some calling the California Model “Prisneyland”, CDCR executives attempted to re-brand the California Model. Instead of turning to science to see how to run a rehabilitation program, CDCR instead gave inmates more happy activities and told staff this is better for them. CDCR staff have been subjected to increased attacks by inmates with a management who does not care to address the issue. It appears many CDCR managers are afraid to implement necessary security measures as to not offend the California Model ideals.

CDCR is using fancy words to explain how Prisneyland is supposed to work. Words like “dynamic security” are used to give inmates more freedoms, “normalization” to make inmates happier in prison, “peer support” to allow inmates to earn good-time credits, and “trauma-informed organization” to give inmates an excuse when they injure staff. Although these California Model catchphrases sound researched, they are not implemented with any type of criminological necessity or scientific backing. The California Model of prison management is only a political toy which is allowing for more violence in prisons and a poke in the eye for the victims of crime.

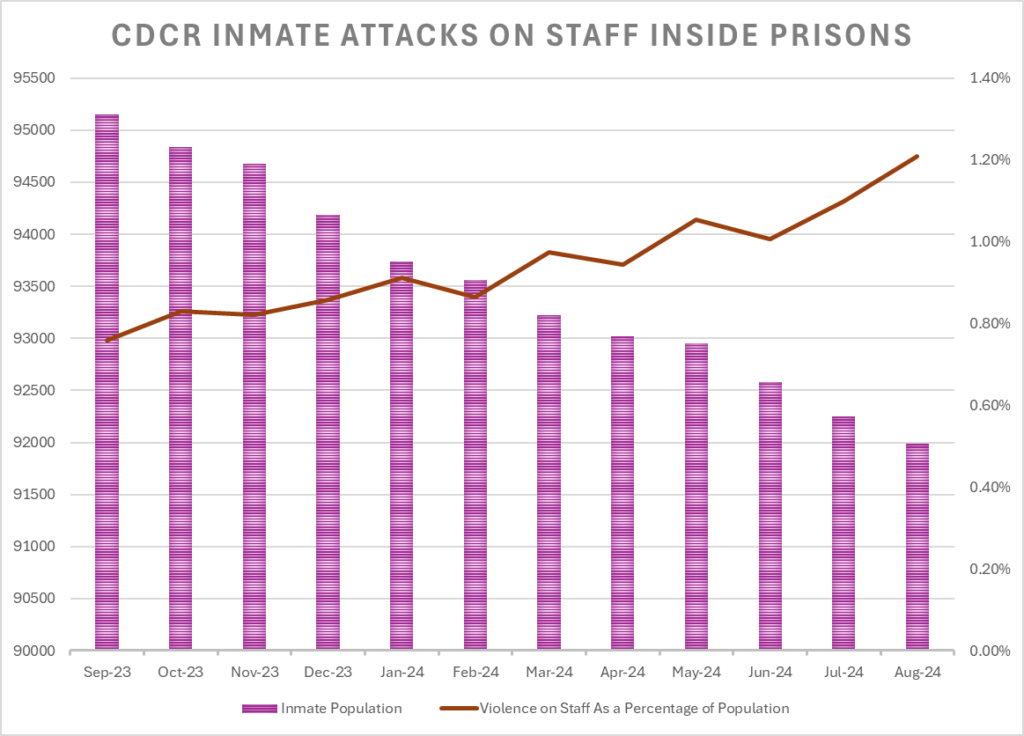

Below is a chart showing the decrease of inmate population in CDCR and the steady increase in attacks on staff members inside the same prisons. The rising trend of violence uses the combined numbers of documents assaults and batteries on staff members divided by inmate population.

Its gotten to the point we cant even say the word “inmate” anymore! They are now to be called “incarcerated persons”. They are actually changing the Title 15 to reflect this. Ive been a c/o for 27 yrs, 10 in the Feds and 17 with CDCR. I used to be proud of the fact i was a sworn peace officer, now im embarrassed to say i work for this department!! Dont get me wrong, its provided a good living and retirement, but i cant wait to get the h-ll out of this job!! These are convicted murderers, rapists, etc. and we are being forced to change policies because we are offending them!! What a joke!! Only in CA. How many other states are following this CA MODEL??!

Don’t forget we had to take the prisoner markings off the state clothing for inmates. Can’t offend the rapists and murderers. I am convinced no other state is stupid enough to follow the California Model of prison management. The California Model makes staff less safe, and negatively impacts crime victims. Unfortunately I think Prisneyland is going to stay for a while because no California politician will admit they were wrong.

We were already doing the “Cal Model” w/o all the “extras” at Chuckies. Loved that place. But also another failure of this Governor and state on closing joints instead of opening more to house these inmates at the state level where they belong, NOT the counties.

As a dentist working within CDCR, I feel compelled to share a frontline perspective on the so-called “California Model.” While the intentions may sound noble on paper and are often presented with a reformist flair, the reality on the ground paints a very different picture—one that is far less idealistic and, in many ways, actively counterproductive. The implementation of this model frequently hinders the very goals it claims to pursue, and the effects ripple across the entire system, from clinical operations to institutional morale.

1. Dynamic security, in theory, is supposed to foster safety through positive staff-inmate interactions. In practice, however, it often looks like custody staff attempting to become “buddy-buddy” with incarcerated individuals. The consequences of this misguided approach are stark. Structure and discipline, a cornerstone of any secure institution, begin to erode. Patients show up late for their appointments, skip them altogether, or become emboldened to push boundaries with little fear of repercussions. What’s meant as security through engagement becomes a form of chaos masquerading as compassion. It weakens the lines that define professionalism, safety, and order. Rules become optional, expectations become negotiable, and the boundaries we rely on to function safely within a correctional setting begin to dissolve. This doesn’t just compromise security; it damages the integrity of care delivery, making it nearly impossible to maintain consistent standards.

2. Normalization is another principle that sounds admirable in a policy paper but becomes problematic in application. What’s considered “normal” for someone living freely in society cannot, and should not, be blindly applied to those in custody. If these individuals had been operating within socially accepted norms, they wouldn’t be incarcerated in the first place. The idea that we can recreate community environments behind bars is not just naïve, it can be actively harmful. It creates an environment with unrealistic expectations that inmates are neither ready for nor capable of meeting, and it confuses staff who are already navigating complex dynamics. The purpose of incarceration includes structured rehabilitation, accountability, and consequences. When normalization becomes a goal, we risk losing sight of the structured support necessary for true rehabilitation. Instead of creating pathways to change, we build illusions that serve no one.

The contradictions are especially glaring when we examine staff versus inmate privileges. Staff are not permitted to carry personal cell phones, check emails, or listen to music during work hours. These rules are strictly enforced under the rationale of maintaining professionalism and focus. Meanwhile, prisoners enjoy access to digital tablets that offer phone calls, video chats, email, and even streaming entertainment. This disparity is so extreme, it becomes offensive to those of us who follow the rules, show up every day, and contribute to society in meaningful ways. It sends a dangerous message: that compliance, diligence, and personal responsibility are less valued than appeasement and superficial equality.

3. Peer support, as endorsed by figures like Kevin Myers and Andrew Elms, is perhaps the most glaring example of ideology over expertise. The idea that incarcerated individuals—who have no formal education or certification—can effectively educate others about oral health is both insulting and dangerous. It devalues the years of training and rigorous licensing that dental professionals undergo. It also tramples on fundamental patient rights, including privacy and the expectation of competent care. We are not operating a Medi-Cal clinic here; we are running dental services within a correctional facility. The environment is unique, the risks are real, and the stakes are high. Allowing inmates into clinical spaces under the guise of being “peer educators” or quasi-providers blurs critical lines of safety and professional responsibility. Labeling inmates as “providers” is not just misleading, it creates a false equivalence that can lead to serious consequences, both legally and ethically. We cannot afford to gamble with safety or credibility in such a high-risk environment.

4. Regarding trauma-informed care, yes—acknowledging trauma is undeniably important. But this acknowledgment cannot remain an abstract ideal or a bullet point in a policy memo. Without meaningful structural change throughout the broader prison system, change that is implemented, monitored, and sustained, the concept remains largely superficial. True trauma-informed care requires a foundational shift in how institutions operate, how staff are trained, and how support systems are built. As it stands, it’s more of a feel-good checkbox than a transformative model. We’re left with diluted initiatives that lack the infrastructure to be effective, further deepening the disconnect between ideals and reality.

It is increasingly evident that this so-called model is being driven not by measurable outcomes, but by ideology. Kevin Myers, Statewide Dental Director, who has not treated a single patient over a decade—continues to shape clinical policy from an administrative perch, reportedly earning half a million dollars annually. His decisions, far removed from the daily grind of actual patient care, feel disconnected and tone-deaf. Local institutional staff meetings no longer center on improving patient outcomes or refining clinical practices; they have become echo chambers for Myers’ political agendas and reformist posturing. There is little to no discussion of clinical excellence, innovation, or practical support for frontline staff. The result is a demoralizing environment for those of us still committed to providing meaningful, high-quality care.

To underscore the disconnection, consider the recent survey distributed to staff, ostensibly to collect honest feedback about working conditions and morale. While the gesture may have been well-intentioned, the follow-up, or lack thereof, revealed its true nature. No tangible changes occurred. No issues were meaningfully addressed. The entire process felt like an exercise in optics, aimed more at checking a bureaucratic box than addressing real concerns. It left many of us feeling even more alienated.

The California Model borrows the language of reform, terms like “dignity,” “compassion,” and “rehabilitation”,but fails to ground those ideals in operational reality. What we need is not more rhetoric, but evidence-based, practical strategies that improve safety, care quality, and institutional integrity. It would help if supervising dentists, health program managers and supervising dental assistants were willing to hear us; but, they are unwilling to listen because they’ve been brainwashed by the ideology. Those of us on the frontlines are not asking to turn back the clock, we are asking to be heard, to be supported, and to practice with integrity in an environment that respects both our expertise and the unique challenges of correctional healthcare. The well-being of our patients and the safety of our colleagues depend on it.